World Wetlands Day: Protecting What Protects Us

February 2 is World Wetlands Day! Not to brag, but Florida is home to the most wetland ecosystems in the continental United States. From the cool canopies of cypress swamps to freshwater marshes like the Everglades, our wetlands are full of life - and they give life to us!

Did you know: Wetlands used to cover more than half of the state? That’s roughly 20.3 million acres.

Today, only about half of these original wetlands are left, wiped out by developed and degradation. It’s up to us to protect them.

Our Florida wetlands are more than just beautiful – they're functional! Wetlands filter water, keeping groundwater healthy for plants, animals, and humans.

Many of Florida’s unique feathered, scaly, and furry friends call wetlands home, from the rare and endangered Florida panther, to stunning birds like ibis and herons, to aquatic species including manatees and tarpons. To protect the critters we share our home with, we must protect the wetlands where they live!

Floridians are no stranger to extreme weather, and wetlands are one of our first lines of defense when hurricanes and storm surges come knocking. Mangroves absorb flood waters and protect against erosion, and swamps are expert water managers, holding flood water and naturally releasing it during droughts. Our wetlands are true (and smart) protectors!

Since our founding in 1999, we’ve protected roughly 45,000 acres of land across Florida from the Panhandle to the Keys — and that includes wetlands! From the coastal marshes of Innerarity Island to the old swamps of Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park, our team works every day to permanently protect our irreplaceable wild lands and the water and wildlife within them.

There’s no better way to fall in love with our wetlands than by experiencing them for yourself! Our team happily hosts events throughout the state where we invite you to adventure through the places you’re helping protect.

Sign up for our newsletter to stay in-the-know about upcoming events where you can experience wild Florida in the company of likeminded supporters and conservationists.

It’s not too late to save our wetlands – to save what saves us. This World Wetlands Day, we invite you to celebrate our precious wetlands join our mission to save Florida's water, wildlife, and wild places - before they’re lost forever.

in case you missed it:

About Conservation Florida:

Conservation Florida is an accredited, nonprofit land conservancy dedicated to conserving the Sunshine State’s water, wildlife, wild places — the places that make Florida home. Since its founding in 1999, Conservation Florida has saved nearly 45,000 acres, serving all 67 counties in Florida, by prioritizing strategic and evidence-based land protection, education, and advocacy. Learn more at conservationfla.org and follow us on social media @conservationflorida.

The Wild Florida 5K – Why We Run

The Wild Florida 5K presented by Uncle Matt’s Organic is almost here!

On Saturday, January 31, lovers of Florida’s water, wildlife, and wild places are invited to join us at Lake Baldwin Park in Orlando for one of our favorite FUN-draisers - the Wild Florida 5K!

But aside from having a wildly fun time, why do we run?

To PROTECT OUR PARADISE

Every day, thousands of acres of irreplaceable, natural land are lost in Florida. This land provides crucial habitat for incredible native species like the alligator, bald eagle, Florida panther, and more. All proceeds from the Wild Florida 5K go back to our land protection mission, and because we can turn $1 into $36 worth of land saved, your steps make a HUGE difference. Every step along the run path helps save the places that matter most!

To Honor Our New Years Resolutions

As we kick off a new year, many of us have goals to move our bodies and do good in our community. You can achieve both by participating in the Wild Florida 5K! Whether you’re speedy like a panther or steady like a tortoise, the scenic, flat path for the Wild Florida 5K is a fantastic way to get your steps in. Plus, your steps will directly help protect more of the wild and working lands that make Florida so special!

To build community

Clear blue waters, oak hammocks, stunning sunsets – and yes, exercising! - are best enjoyed with the ones you love. So gather your wild crew and join us at the Wild Florida 5K! You’ll be in good company surrounded by other conservation-minded walkers and runners passionate about saving this place we call home, so you might even make some new friends, too. Plus, the course is just 3 miles – more than enough time to catch up with your loved ones while you make a difference together!

Got a friend who should join you at the starting line?

Share the code FloridaFriend to give them a special discount on their registration!

To get inspired

It can be hard to see the places we know and love disappearing in front of our eyes. The orange groves by your home are becoming luxury living; the thick forests being paved. But we know that there are people all around us who care about protecting these places before they’re gone forever – people just like you! The Wild Florida 5K is an opportunity to champion conservation efforts and have fun while doing it.

Register today, and we’ll see you on the course!

- Team Conservation Florida

in case you missed it:

About Conservation Florida:

Conservation Florida is an accredited, nonprofit land conservancy dedicated to conserving the Sunshine State’s water, wildlife, wild places — the places that make Florida home. Since its founding in 1999, Conservation Florida has saved nearly 45,000 acres, serving all 67 counties in Florida, by prioritizing strategic and evidence-based land protection, education, and advocacy. Learn more at conservationfla.org and follow us on social media @conservationflorida.

Week of Gratitude: Celebrating the People Who Help Protect Wild Florida

With Thanksgiving approaching this week, we’re celebrating the gratitude we feel all year round for our beautiful, one-of-a-kind home … and all those we share it with. Since opening our doors, we’ve now conserved nearly 45,000 acres from Pensacola to the Florida Keys.

But one thing’s for sure: We could not do this conservation work alone.

Protecting the places that make Florida Florida takes all of us. The prairies and pine flatwoods, the winding rivers and beautiful beaches. Room for our prowling panthers and beloved scrub jays.

During our Week of Gratitude, we’re celebrating the people who make this conservation work possible!

To Our Landowners:

You’re leaving the ultimate legacy.

Whether you’re safeguarding working lands, preserving sensitive ecosystems, ensuring wildlife have room to roam, or leaving a legacy for your family, your decision to conserve your property is a gift to all Floridians.

To Our Donors:

You fuel every acre we protect.

Your generosity turns opportunities into real land saved. And not just saved but stewarded forever and safeguarded for future generations. Whether you’ve given once or given annually and joined Club 1845, we’re so grateful.

To Our Volunteers:

You remind us that conservation is a work of heart.

From building trails at D Ranch Preserve to joining bioblitzes at Bellini Preserve to lending your time at community events, you show up. Florida is better because of your commitment, curiosity, and willingness to get a little dirty for a great cause. Thank you for your hard work to care for this place we all love so much.

To Our Partners

Your collaboration multiplies our conservation impact.

Our work is strengthened by incredible partners! From local and statewide governments to foundations, businesses, and fellow nonprofits - none of our permanent conservation work would be possible without the support of our partners. We believe in the power of partnerships. Here’s to many more acres saved!

While Florida is special in too many ways to count, we believe all of you are the very best part. Thank you for your support, big or small, today & every day. We couldn’t do this work without you!

Happy Thanksgiving!

Team Conservation Florida

in case you missed it:

About Conservation Florida:

Conservation Florida is an accredited, nonprofit land conservancy dedicated to conserving the Sunshine State’s water, wildlife, wild places — the places that make Florida home. Since its founding in 1999, Conservation Florida has saved nearly 45,000 acres, serving all 67 counties in Florida, by prioritizing strategic and evidence-based land protection, education, and advocacy. Learn more at conservationfla.org and follow us on social media @conservationflorida.

Tour de Coast: Mak’s 550-Mile RIDE for Conservation Florida

All photos provided by Mak

This October, one determined cyclist is taking on the ultimate Florida ride - and she’s doing it for

wild Florida.

Meet Makayla “Mak” Fick, an endurance athlete from Jacksonville Beach who’s trading her daily training rides for a roughly 550-mile, three-day journey from Jacksonville Beach to Key West. Her mission? To raise awareness and funds for Conservation Florida and our work protecting the lands and waters that make Florida home - for people, for nature, forever.

From Her Hello Kitty Bike to 500 Miles

Mak’s love for cycling started early - with the smell of rubber tires, the thrill of speed, and a Hello Kitty bike that she begged her dad to take the training wheels off of. From biking to school every day to outpacing her dad up hills, cycling became more than just transportation - it was joy, challenge, and freedom.

After running at Ole Miss and immersing herself in Jacksonville Beach’s endurance sports community, Mak decided she was ready for her biggest “side quest” yet: Tour de Coast.

Why She’s Riding for Wild Florida

What she’s named the Tour de Coast isn’t just about miles - it’s about mission. Mak was inspired by Conservation Florida’s work to protect Florida’s wildlife corridors, including the Guana River Wildlife Management Area, a critical habitat and recreation area we helped protect from a land swap earlier this year. That victory preserved not just a safe haven for wildlife, but also a beloved route for gravel cyclists and nature lovers alike.

“Cycling has given me so much joy and connection,” Mak says. “I wanted to use this ride to give back - to protect the places I love to explore and help others experience them for years to come.”

Mak’s route across the Sunshine State.

The Ride

From October 24–26, 2025, Mak will pedal the length of Florida in just three days, connecting with local bike shops and fellow cyclists along the way. Each mile she rides will shine a spotlight on Florida’s wildlife corridors - the connected lands that allow animals like the Florida panther, black bear, and countless bird species to roam freely and safely.

“I wanted to use this ride to give back - to protect the places I love to explore and help others experience them for years to come.”

- Mak Fick

How You Can Support Mak’s Mission

Mak has set a fundraising goal to support Conservation Florida’s mission to protect Florida’s wild and working lands. Here’s how you can be part of the Tour de Coast:

Donate to her GoFundMe → Support the Tour de Coast

Follow her journey → Event Details & Updates

Share her story on social media to help spread the word.

Every dollar raised helps us protect the lands and waters that make Florida the paradise we call home.

Together, we can keep Florida wild - for wildlife, for people, and yes, for cyclists!

in case you missed it:

About Conservation Florida:

Conservation Florida is an accredited, nonprofit land conservancy dedicated to conserving the Sunshine State’s water, wildlife, wild places — the places that make Florida home. Since its founding in 1999, Conservation Florida has saved nearly 45,000 acres, serving all 67 counties in Florida, by prioritizing strategic and evidence-based land protection, education, and advocacy. Learn more at conservationfla.org and follow us on social media @conservationflorida.

A SAFE PLACE TO LAND

Photos provided by Anna Crocitto, Tim Barker, and Avian Research and Conservation Institute (ARCI)

If you’ve ever looked up on a summer day in Florida and spotted a black-and-white bird with a forked tail gliding effortlessly against the blue sky, chances are you might’ve seen a swallow-tailed kite. These graceful birds, sometimes called “sky angels,” travel thousands of miles each year, chasing warm winds and plentiful food.

You might have even seen a special kite named “Townsend!”

Why so special, you may ask?

This swallow-tailed kite checked in for a stay amongst a pine forest permanently protected by Conservation Florida near Ocala in Central Florida.

You could say he’s pretty close to our hearts.

Townsend is part of a tracking study led by the Avian Research and Conservation Institute (ARCI), which follows these birds on their remarkable journeys to better understand their migration patterns and the habitats they depend on.

Townsend was the last of the GPS-tracked swallow-tailed kites to begin his fall migration. On August 27, he set out on his journey!

He started south from the Savannah River in Georgia, spending his first night along the Altamaha River, a familiar area near his nesting territory.

From Georgia, he continued south to our home state of Florida where he found a peaceful refuge on Conservation Florida-protected land in Marion County - our Millpond Swamp conservation easement.

Townsend’s flight path southward, including a rest at Millpond Swamp.

On Millpond Swamp, he battled no bright streetlights or racing cars. Only the buzzing of bugs and the fresh fog of the morning.

A peaceful moment of his journey south.

For Townsend, Millpond Swamp offered a safe place to rest and refuel. For us, his visit is a reminder of why land conservation matters.

Swallow-tailed kites rely on Florida’s wetlands, forests, and open spaces to find food, raise their young, and safely migrate each year. When we protect those places, we’re not only safeguarding one species; we’re protecting entire ecosystems.

Florida is the stronghold for swallow-tailed kites in the United States. Once nesting in 21 states as far north as Minnesota, their numbers have declined sharply over the last century, with only about 15,000 remaining today. Most now breed here in Florida, making our state essential to the future of the species. By late summer, the young are ready to take flight, and the flocks begin to gather before making their long journey back to South America.

Most swallow-tailED kites now breed here in Florida, making our state essential to the future of the species.

For kites like Townsend, protected wild places aren’t a luxury - they’re a necessity.

Wetlands provide the frogs and insects that sustain them, tall trees offer nesting sites, and large forests give them space to rest before migration. As development and habitat loss continue, conserving these connected, protected spaces becomes even more urgent.

Conservation Florida’s work ensures that birds like Townsend have safe places to land - today, tomorrow, and forever. Through land conservation, we’re helping keep the skies full of these “sky angels.”

When Townsend soared over our protected land, he showed us what’s at stake - and what’s possible when we work together to keep Florida wild.

By September 1, Townsend had reached Cuba, where he stayed for four nights before flying to Cancún, Mexico. He has spent the past few weeks in Mérida, Mexico, and we expect him to continue south to South America soon.

We’ll be looking to the skies next season, hoping to see him again on his journey home.

Thank you to the partners who shared this story with us and are helping swallow-tailed kites like Townsend soar!

American Bird Conservancy (ABC)

The Avian Reconditioning Center for Birds of Prey

Cellular Tracking Technologies CTT GSM-GPS transmitters

Georgia Department of Natural Resources (GADNR)

Microwave Telemetry, Inc. Satellite transmitters

National Fish and Wildlife Federation (NFWF)

Orleans Audubon Society (OAS)

Ornitela GSM-GPS transmitters

PotlachDeltic Corporation

*Swallow-tailed Kites are captured, banded, and fitted with a trackers under State, Federal, and local permits held by the Avian Research and Conservation Institute (ARCI). ARCI partnered with American Bird Conservancy and Orleans Audubon Society to track kites like Townsend through funding from International Paper and the National Fish and Wildlife Federation. More on ARCI’s blog: https://www.arcinst.org/2025/07/17/swallow-tailed-kite-research-coalition-continues-to-improve-sustainable-forests-in-the-southeastern-u-s/

in case you missed it:

About Conservation Florida:

Conservation Florida is an accredited, nonprofit land conservancy dedicated to conserving the Sunshine State’s water, wildlife, wild places, and connecting a functional Florida Wildlife Corridor. Since its founding in 1999, Conservation Florida has saved more than 40,000 acres, serving all 67 counties in Florida, by prioritizing strategic and evidence-based land protection, education, and advocacy.

Follow us on social media @conservationflorida.

Leave Your Legacy: National "Make a Will" Month

We know — writing a will isn’t exactly at the top of anyone’s summer to-do list.

But joining the Florida Land and Legacy Society now will mean a healthier, greener Florida tomorrow.

As we recognize National Make-A-Will Month, we’re inviting you to consider leaving a legacy gift to Conservation Florida. It’s a powerful way to ensure that the wild places you love — the springs, ranchlands, forests, and swamps — continue to thrive long after we’re gone.

And here’s the incredible part:

Every $1 given to Conservation Florida becomes $36 in land protected — thanks to leveraged funding and strategic maneuvering from our team.

Your legacy gift could have an extraordinary impact.

Photo credit: Anna Crocitto

Ways to leave Conservation Florida in your will:

Bequests — Add a simple clause in your will or trust.

Securities — Donate appreciated stocks or mutual funds.

Life Insurance — Name us as a policy beneficiary.

Retirement Plans — List Conservation Florida as a beneficiary on your IRA or 401(k).

Real Estate — Leave land that can be conserved or used to fund protection elsewhere.

Charitable Trusts & Annuities — Create a giving plan that benefits both you and conservation.

No matter your age or assets, there’s a way to leave a lasting impact.

Photo credit: Anna Crocitto

If you have already included Conservation Florida in your estate plans or would like to speak with a member of our philanthropy team about your legacy, please call 352-376-4770 ext. 701 or email at philanthropy@conservationfla.org — we're happy to help.

Together, we can make sure that a century from now, wild Florida is still wild — and still here.

Thank YOU for thinking about the future of this beautiful state we all call home.

in case you missed it:

About Conservation Florida:

Conservation Florida is an accredited, nonprofit land conservancy dedicated to conserving the Sunshine State’s water, wildlife, wild places, and connecting a functional Florida Wildlife Corridor. Since its founding in 1999, Conservation Florida has saved more than 40,000 acres, serving all 67 counties in Florida, by prioritizing strategic and evidence-based land protection, education, and advocacy.

Follow us on social media @conservationflorida.

A Wild Florida Summer Thanks to you!

Because of you, this summer has been

wildly amazing!

From protecting panther habitat to opening new trails, your support turned hot summer days into huge conservation wins.

Mind if we share some highlights?

Here’s just some of what you made possible:

🌿 You helped conserve AP Ranch — 1,003 acres of working lands in Highlands County, home to endangered Florida panthers. This land will remain forever wild, thanks to your support.

🚶♀️ You also helped connect people to the land. In May, we opened 3.5 miles of hiking trails at D Ranch Preserve in Volusia County — a once-private ranch that’s now permanently protected and open for all to explore.

🏆 You helped us tell Florida’s conservation story — and win an Emmy doing it! Our docuseries, Protect Our Paradise, took home a Suncoast Emmy Award, and we couldn’t have done it without you.

🎉 Our Sunshine State Soirée was a sold-out success! Together, we raised over $220,000 to protect Wild Florida. From cocktails to conservation, we celebrated the future we’re building — with you at the center.

Photo credit (left to right): Anna Crocitto, Conservation Florida, Brandon A. Güell

But that’s not all…

💧 You ensured that the largest underground cave system in the United States is protected forever. Chip’s Hole in Wakulla County was saved from development and will now become a preserve for public use and recreation, all thanks to your voices.

🏛️ We took your voice to Tallahassee. At our legislative reception, we brought lawmakers, landowners, and advocates together to champion land conservation and policy that supports protecting wild and working lands.

📝 Our summer interns have been hard at work at D Ranch Preserve — helping restore trails, document wildlife, and support public access. On our blog, intern Raylynn shared a powerful reflection on conservation, connection, and what it means to grow up in Florida.

🐻 Conservation Florida made headlines! News outlets featured our work to give black bears room to roam, highlighting the importance of corridor connectivity and protecting habitat before it's gone.

🌱 And there's more good news: Our Private Lands Stewardship Program is officially serving landowners — empowering Floridians across the state to conserve the places that matter most.

Photo credit (left to right): Carlton Ward Jr., Brandon A. Güell, Chris Werner

And through it all, your impact multiplied. Every $1 you give helps save $36 worth of Wild Florida — protecting more land, more wildlife, and more of what makes this state special. We’re just getting started — and we’re so glad you’re on this journey with us.

Stay cool, and stay wild,

The Conservation Florida Team

in case you missed it:

About Conservation Florida:

Conservation Florida is an accredited, nonprofit land conservancy dedicated to conserving the Sunshine State’s water, wildlife, wild places, and connecting a functional Florida Wildlife Corridor. Since its founding in 1999, Conservation Florida has saved more than 40,000 acres, serving all 67 counties in Florida, by prioritizing strategic and evidence-based land protection, education, and advocacy.

Follow us on social media @conservationflorida.

From Cattle to Conservation: The Role of Ranchlands in Florida’s Environmental Future

by Raylynn M. Adcock, Conservation Florida Summer Intern

When most people picture conservation in Florida, they imagine wetlands, springs, or thick forests, typically not open pastures. As a student at the University of Florida studying animal sciences and agricultural communications, I’ve learned that agricultural lands are more than just farmland. Through my time walking pastures, watching cattle roam, attending events like the Florida Cattlemen’s Convention to talk with ranchers who’ve cared for these spaces for generations, and especially during my internship this summer with Conservation Florida, I’ve seen that these working lands are crucial to Florida’s environment, economy, and way of life.

Until 2019, when D Ranch Preserve was officially protected by Conservation Florida, the land was home to a cow-calf operation. At first glance, D Ranch Preserve may look like any other cattle operation or ranch, but spending time on the land has deepened my understanding of just how much it supports. Working at D Ranch Preserve has shown me firsthand what many already believed to be true: working lands aren't barriers to conservation, they’re the backbone of it. Across Florida, places like D Ranch Preserve are proving that agriculture and conservation can exist not only side by side but in direct support of one another for the betterment of saving wild Florida.

Florida’s ranchlands are more than just grazing space for cattle. They provide vital habitat for wildlife, help keep water clean by soaking it back into the ground, and act as natural buffers against the rapid spread of development. As more houses and highways continue to sprawl across the state, protecting places like D Ranch Preserve feels more pressing than ever.

“Florida’s ranchlands are more than just grazing space for cattle. They provide vital habitat for wildlife, help keep water clean by soaking it back into the ground, and act as natural buffers against the rapid spread of development.”

I’ve witnessed the balance firsthand. Early in the mornings, I see dew fresh on the grass and whitetail deer silently slip through the trees. Nearby, a gopher tortoise disappears into its burrow as a crowd passes it on our guided nature hike. Overhead, sandhill cranes call out in their distinctive voices and their bellowing calls echo through the wide-open sky. As I walk the trails at D Ranch, the smell in the air is a mix of sun-soaked grass and damp earth, leaving me with a warm and earthy feeling of appreciation for the land.

D Ranch sits along a natural path used by many animals to travel safely between ecosystems and fields. It’s like a quiet highway for wildlife, hidden in plain sight. This connection allows animals to roam freely and find food, mates, and shelter essential for their survival. Cattle still graze here too, which adds to the richness of this landscape and reminds us that working lands and conservation lands don’t have to be separate. We’re stronger when we work together, when ranchers, conservationists, and nature itself all play a role in protecting these places.

“Organizations like Conservation Florida work with landowners to protect their land for the future by keeping it natural and undeveloped, while still allowing it to be used for ranching or farming. ”

What stands out to me most about D Ranch Preserve is the way it redefines what conservation can look like. It’s not about taking people off the land or halting production. Instead, it’s about protecting the land’s ability to thrive, even as its role evolves. Organizations like Conservation Florida work with landowners to protect their land for the future by keeping it natural and undeveloped, while still allowing it to be used for ranching or farming. This means families can stay and care for their land, keeping it wild and open for the future.

As I continue learning and gaining experience, I’m more certain than ever that the world we live in today is one in which agriculture and conservation are not only compatible but essential partners. D Ranch Preserve shows what’s possible when we stop seeing these sectors working against one another. At D Ranch Preserve, raising cattle and protecting wildlife are one and the same because here in Florida, agriculture and conservation grow from the same soil. Even more so, the people who work this land are the original conservationists, caring for the soil, water, and animals that depend on it.

If we want to protect Florida’s future, we need to continue working together by listening, learning, and protecting the land that sustains us all.

in case you missed it:

About Conservation Florida:

Conservation Florida is an accredited, nonprofit land conservancy dedicated to conserving the Sunshine State’s water, wildlife, wild places, and connecting a functional Florida Wildlife Corridor. Since its founding in 1999, Conservation Florida has saved more than 40,000 acres, serving all 67 counties in Florida, by prioritizing strategic and evidence-based land protection, education, and advocacy.

Follow us on social media @conservationflorida.

Sending the Blues Away

For nearly a decade, no one could find a Miami blue and it was eventually feared extinct. Then, an observant butterfly aficionado at Bahia Honda State Park noticed a butterfly that looked different than any they had seen there before. It was a Miami blue!

by Peter Kleinhenz

“Doomed to extinction,” “irreversible decline,” “extinction is forever.” Those words are like lightning bolts that strike down periodically from the clouds of depression that follow me in the wake of animal extinctions. Species that have taken millions of years to evolve to their current state disappear, in some cases, in just a few generations due to habitat loss, invasive species or poaching. Nothing makes me sadder or more pessimistic.

Few intact coastal habitats remain in the Florida Keys. Photo by Geena Hill.

A pair of Miami blue butterflies mating. Photo by Florida Museum of Natural History.

Miami blue butterflies in captivity start their lives as tiny caterpillars in little plastic cups. Photo by Florida Museum of Natural History.

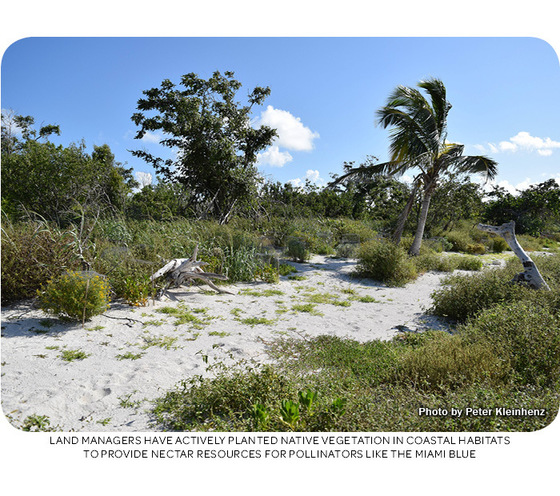

Land managers have actively planted native vegetation in coastal habitats to provide nectar resources for pollinators like the Miami blue. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

Miami blue caterpillars are tiny and delicate, and extreme care must be taken during their reintroduction. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

A Miami blue caterpillar explores its first wild leaves after its reintroduction. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

Wild cage protects planted dune vegetation. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

Sarah Steele Cabrera shows a young Miami blue to a nearby landowner. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

Researchers at the University of Florida prepare tiny habitats for young Miami blue butterflies. Photo by Tedd Greenwald.

Ants help protect the Miami blue from predation, while “farming” the caterpillars for their sweet secretions. Photo by Genna Hill.

The good news is that the electrified words mentioned above are not always true. Take the Miami blue butterfly. This diminutive insect once ranged from Tampa Bay south to Key West, fluttering from flower to flower in dry, coastal habitats. Miami blue females lay up to 300 eggs and, historically, they were limited only by the availability of their host plants and predation. Then humans came along.

Dry, coastal habitat equated to prime real estate for many, and it didn’t take long for Miami blues to disappear from virtually all of their historic range. The reason for this decline stems from an unfortunate aspect of Miami blue mobility. The butterflies rarely range away from the beach vegetation where they first emerged out of eggs. Once habitats became fragmented from one another, the chances of a Miami blue finding a non-sibling mate were almost impossible. By the time I was born in 1990, this butterfly could only be found among the vegetation along a few undeveloped beaches in the Florida Keys.

Then Hurricane Andrew hit. The Category 5 hurricane slammed into South Florida in 1992, obliterating much of the remaining habitat of this tiny insect. Under natural circumstances, populations in destroyed areas would be replenished by other populations nearby. This was no longer possible and, so, with the hurricane went the Miami blue.

For nearly a decade, no one could find a Miami blue and it was eventually feared extinct. Then, an observant butterfly aficionado at Bahia Honda State Park noticed a butterfly that looked different than any they had seen there before. It was a Miami blue! Subsequent surveys showed that approximately 50 Miami blues survived in less than 1 square mile of habitat.

Conservationists immediately rushed into action.

Wild specimens were collected and lepidopterists who study butterflies at the University of Florida created a captive breeding colony. The plan from the beginning was that offspring from this group would be used to create new populations in suitable habitat. But, first, you need suitable habitat.

Miami blues, like all butterfly species, rely upon certain plant species that serve as “hosts” for their caterpillars. These little munching machines have a voracious appetite for gray nickerbean, blackbead and balloonvine. The adults are more liberal in their food choices, sipping nectar from many types of flowering plants. As such, there is a direct link between healthy wildflower populations and healthy pollinator populations. This fact has informed the management of an area that will likely become crucial to the Miami blue butterfly’s survival.

Florida Keys Wildlife and Environmental Area (WEA) consists of 4,250 acres, scattered from Key Largo to the Lower Keys. Some of these acres represent pristine examples of imperiled natural communities. Others have a long way to go. One such site, a degraded beach on Sugarloaf Key, was covered in an exotic plant known as scaevola. But area biologists Jeanette Parker and Susie Nuttall saw potential and got to work.

“Whenever we plan a planting project, the first thing we do is identify the habitat type such as hardwood hammock, coastal berm, mangroves, etc.,” Susie explained. “I take inventory of what native vegetation is already growing there, how well it is doing and what its sun, soil and water requirements are. This allows me to create a list of species that should be growing on the site. From this list, I then narrow it down by what plant species are threatened or endangered, which plant species will benefit wildlife species that are threatened or endangered and, in the case of this beach site, I look at what species will provide increased beach stabilization.”

Planting a variety of plant species helps the many wildlife species that depend upon these plants. One species that Florida Keys WEA biologists had their sights set on from the beginning was the Miami blue.

“Every organism that is associated with an ecosystem plays a vital role to the health and stability of that ecosystem,” Susie elaborated. “When one piece of the ecosystem is missing, often unintended or unknown negative impacts occur and sometimes we don’t realize it until it’s too late. Butterfly species, such as the Miami blue, are believed to be better pollinators than bees. Recent studies show that we are seeing large declines in insect populations, so we hope that by creating the conditions to restore one species, we can benefit other species as well.”

Susie and Jeanette planted a suite of species onsite to do just that. They surrounded the plants with wire cages to protect them from hungry (and nonnative) green iguanas. And then the wait for the missing pollinators began. It lasted until a fortunate set of circumstances unfolded, right when I happened to be in the area.

A few weeks ago, I was down in the Keys with my coworkers to conduct site visits for new visitor projects in the area. The three of us were working on things that weren’t article-worthy when Jeanette, the lead area biologist, received an exciting phone call. It turned out that the woman on the other end of the line, Sarah Steele Cabrera, is a lepidopterist at the University of Florida and she had some leftover Miami blue caterpillars from another project. Did Jeanette want some?

Of course she did, and she kindly invited Catalina, Melissa and me to take part. Just a couple days later, we met Jeanette and Susie early in the morning for a small-scale, but significant, act of conservation.

We reached the end of a road in a neighborhood right by the coast. Sarah met us there, along with a landowner whose property bordered the patch of coastal habitat we would be visiting. I watched as Sarah, Susie and Jeanette talked with the landowner about the value of conserving Miami blues and restoring habitat. The evidence that conversations like this matter surrounded us. Native pollinator plants, water features and bird feeders indicated that this landowner wanted his home to be an extension of the natural ecosystem that surrounded him.

Sarah went to her car, grabbed some foam cups and held them out for us to see. She peeled back some netting to reveal a cluster of small leaves and even smaller caterpillars. They were Miami blues and were at the end of a lengthy journey.

Students in the University of Florida lab of Dr. Jaret Daniels have been raising Miami blue butterflies in captivity to provide stock for future releases. A couple of weeks before our visit, such a release occurred at Long Key State Park. The cup Sarah held in her hand housed “leftovers.” The little green and brown specks didn’t look like much but, after Sarah gave us more details how these caterpillars got here, we didn’t doubt their value.

Susie added, “When we read articles about [Miami blue] reintroductions, like the recent one at Long Key State Park, we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg. The process is a long road and includes an immense amount of work from dedicated people to get funding, raise thousands of larvae in a lab, monitor wild populations and coordinate between various institutions and agencies, permit applications, etc.”

The six of us trudged through vegetation that ultimately opened up onto a beach, facing the deep blue water that separated us from Cuba by only 100 miles. The beach was punctuated by metal cages that surrounded unusual plants including sea lavender, Joewood and inkberry. These, Susie noted, were planted just a few months ago. All were spreading beyond their cages, establishing themselves on one of the few truly natural beaches in the area. The stage was set. The only thing missing were the actors.

Sarah walked Susie and me up to some gray nickerbean. She opened the cup, took out a small paintbrush and allowed a caterpillar to crawl onto the bristles. Sarah then placed the brush next to some leaves and prodded the caterpillar to crawl onto the first wild vegetation it had ever felt.

We collectively scattered caterpillars on any gray nickerbean or Florida Keys blackbead we found until Sarah’s little cup was empty. Now, the caterpillars were on their own. Well, sort of.

Miami blues have a symbiotic relationship with certain ants that keep them safe from marauding parasitic wasps. In return, the ants “milk” the caterpillars for sweet secretions. The team hopes that ants will find these reintroduced caterpillars and keep them safe for the month or so that it takes for them to transform into butterflies. While not necessarily essential to Miami blue survival, this relationship illustrates the fact that reintroductions consist of more than simply releasing a bunch of animals back into the wild. Any animal's strand in the web of their ecosystem must be fully considered for a reintroduction to truly succeed.

I’ve thought a lot about that morning since it happened. I, and many others who work for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), consider conserving wildlife to be the prime motivator for why we are in this field. To take part in it so directly was immensely rewarding and restores my faith that maybe we can turn around the current trend of species extinctions.

I asked Susie several days after the reintroduction what she thought about it. She told me simply, “Being part of a reintroduction of a species that was once thought to be extinct is and will be one of the highlights of my career.”

I’d have to agree. For it seems, with creativity and dedication, extinction can sometimes be just temporary.

Discover more details about the

University of Florida’s work to conserve butterflies:

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/miami-blue/

FWC has numerous resources to learn more about butterflies and ways to help their populations. Visit the Great Florida Birding and Wildlife Trail website to find places to observe butterflies and get rewarded for finding new species. For tips on observing butterflies in one of the best places in the state to see them, visit the Big Bend WMA Butterfly Guide page.

Be sure to join our Pollinators of Florida project on Florida Nature Trackers to add your observations to our statewide database. Finally, you can help butterfly populations by planting a refuge for wildlife or joining us in our Backyards and Beyond campaign.