The State of our State: a Bird's Eye View

As we quickly gained altitude, the trees below multiplied into forests, houses sprouted into neighborhoods, and the roads became snaking masses cutting through the land.

View of the Silver River from above.

Article and Photos by Tanner Diberardino

Edited by Marlowe Starling

Why I loved and hated seeing Florida from above

As a college senior on the cusp of graduating with the hopes of working for an environmental nonprofit, I had admittedly become a bit cynical about my job prospects. That is, however, until I received an email from the assistant director of Conservation Florida about a possible internship. About a week after opening that email, I found myself sitting in the copilot’s seat of a plane (that I was way too large for) with Traci Deen, the executive director, and Butch Parks, the director of conservation. Quite the first day as an intern.

Traci Deen, Conservation Florida’s executive director standing with pilot, Charlie Martinez on flight day. The flight was arranged courtesy of Southwings, which is “a non-profit conservation organization that provides a network of volunteer pilots to advocate for the restoration and protection of the ecosystems and biodiversity of the Southeast through flight.”

That morning, I arrived at the hangar weightless with disbelief but weighed down by about 30 pounds of camera gear. In the lobby, Butch splayed a map over the table and reviewed our flight plan with our pilot, Charlie Martinez, as he snacked on hard-boiled eggs and told tales of his days in the Air Force. I was briefed on which areas were important to photograph, and with that we climbed into the plane. I squeezed into the front seat with Charlie and started to get my cameras and equipment ready for the flight as we taxied out to the runway.

I had flown in a small plane once before, but the experience of taking off still felt unfamiliar and exciting to an exclusively commercial flyer. As we lifted off, the plane bounced and swayed as if it were lifted by a string. I started recording on my GoPro, got my two photo cameras powered on and set up, and grabbed my video camera just in time to catch our departure from Earth.

Capturing the Views

In just seconds, the horizon emerged behind the expanse of wild Florida. The thin haze that hung over the Orlando Executive Airport earlier that morning had lifted, and we were treated to a sunny sky with only a few wispy clouds hanging in the distance. With no air-conditioning in the plane and the sun beaming in through the windows, I had to keep wiping sweat off of my camera, but it was worth it; the sun illuminated the landscape brilliantly and made my job a lot easier.

As we quickly gained altitude, the trees below multiplied into forests, houses sprouted into neighborhoods and the roads became snaking masses cutting through the land. Butch and Traci were rattling out names of rivers and forests one after the other as I snapped away, trying to keep up: the Wekiva River, St. Johns River, Lake Monroe. I tried to take as many photographs of the land as possible while also creating interesting compositions to highlight the unique beauty of this bird’s eye view.

Water from the Withlacoochee River flows into Princess Lake.

Once we reached cruising altitude at 1,200 feet, Charlie slowed and steadied the plane, and the beauty of Florida’s wilderness came into focus. The forest was split in two by the Wekiva River as it glimmered in the late morning light. Vast prairies opened up into lakes and streams, and tiny white dots came and went as airboats weaved throughout the wetlands. Seeing Florida like this truly shocked me and affirmed everything I had heard about how lush and biodiverse this state is. I was taken aback by the sheer scale of the landscape, with swamps and grasslands running for miles and miles. I remember telling Traci, “I wish everyone could see Florida from the air, because then we’d have a much easier time saving it,” and I truly meant it. Unlike the rolling hills and towering mountains of the American West, much of Florida’s beauty is tucked away behind walls of trees, invisible because of its flatness.

Seeing the Big Picture

My job on this flight wasn’t merely to photograph the amazing beauty of Florida, but also to tell the story of how that same land is under threat from overdevelopment. This is a fact that became evermore obvious as the beautiful rivers and prairies became speckled with houses and dissected by highways. Bridges of various sizes straddled rivers, roads cut through previously remote forests, and housing developments consumed patches of green, slowly choking them until there were none left. I saw trees being leveled and burned to make room for new development, while other housing developments only miles away sat baron with only a few houses having ever been built in the entire neighborhood. It was much worse than I thought.

A housing development being built near Clermont, Florida.

Cook Lake surrounded by encroaching development.

An RV resort built only a few hundred feet from the banks of the Ocklawaha River

As a lifelong Floridian, I was familiar with the high amount of development in our state, but I was wholly unaware of the scale. The same size and grandeur of the Florida wilderness that awed me minutes prior now terrified me as I saw it replaced with a congruent cluster of housing developments and highways.

Seeing the state broken up into segments by roads and developments reminded me of an article I had read years ago about the Florida panther. This segmentation breaks up the panther population into smaller groups that can’t access each other, forcing them to breed within those smaller populations. In an article for Wired Magazine, Brandon Keim explains that years of this has caused the eastern panther population to become “riddled with genetic defects and too inbred to survive much longer.'' Unfortunately, it doesn’t end with apex predators like the panthers, as habitat loss is one of the biggest threats to the variety of life on this planet. The International Union for Conservation of Nature produces the most comprehensive list of threatened species globally called the Red List, and according to the WWF, habitat loss is the primary threat to 85% of the species on the list.

Protecting Florida’s Biodiversity

This puts Florida in a particularly concerning spot. We live in one of the most biodiverse areas of the world, and also face high rates of development with nearly 29,000 new homes built last year in Orlando alone according to the Orlando Sentinel. So concerning, in fact, that the state falls within one of only 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world, which are regions home to at least 1,500 endemic vascular plants and greater than 70 percent habitat loss.

All of this information points to the fact that it is imperative that we are thoughtful and think critically about the future of Florida. We cannot continue to grow at this rate with this little foresight and expect to maintain the wild spaces that drew so many here in the first place. Developers with little-to-no accountability for the land they build on are controlling the future of Florida and shifting the landscape in ways that cause permanent damage. We must protect and conserve Florida’s wild spaces while also adapting our already developed land into places of smart and responsible growth.

The St. Johns River, Konomac Lake, and Lake Monroe (From nearest to farthest)

I feel extremely grateful and privileged to have taken that flight and to have seen Florida from this new angle. This perspective is as inspiring as it is educational; there is just as much to learn from seeing the state’s unbridled beauty as there is from seeing the destruction it faces. Efforts from groups like Conservation Florida are the reason that over nine and a half million acres of land are currently being managed for conservation, and the reason I find any solace in our state’s future. A future where we are smarter about how we manage our land, and no longer have to worry about driving countless important species towards extinction.

One of Conservation Florida's ongoing projects: Triple S Ranch

Conservation Florida is working to save Florida’s natural and agricultural landscapes – for nature, for people, forever! We work statewide to protect land that supports native plants and wildlife, fresh water, conservation corridors, family farms and ranches, the economy, and nature-based recreation. Please support conservation by making a donation today.

We would like to extend a very special “thank you” to Southwings for making this flight possible. Southwings promotes conservation through aviation.

A peaceful day at Lake Woodruff National Wildlife Refuge

As our nation’s population continues to grow, more forests and marshlands are destroyed, and more species have become endangered. A refuge is a protected place where wild creatures can live undisturbed by humans.

Written by David Kyle Rakes

Adapted for Conservation Conversations by Marlowe Starling and Cyndi Fernandez

Designated one of “Florida’s Special Places,” the West Volusia Audubon Society offers guided walks at Lake Woodruff on Sundays in the winter. Photo by the Florida Audubon Society.

Lake Woodruff National Wildlife Refuge is located northwest of Deland, Florida and is well known for its lakes, marshes, waterfowl and migratory birds. The openness of this wetland, with its almost treeless expanse of water and grass, makes for a glorious and captivating place.

As our nation’s population continues to grow, more forests and marshlands are destroyed, and more species have become endangered. A refuge is a protected place where wild creatures can live undisturbed by humans.

The first refuge was started here in Florida in 1903 by President Theodore Roosevelt. The three-acre Pelican Island on the Atlantic coast became a protected place for birds. The president was then concerned about native birds that were being killed because of a fashion craze for hats made from their feathers. Today, there are 567 National Wildlife Refuges covering more than 146 million acres of land as of September 2018, and they exist in every state of the United States.

The lake and refuge were named in honor of Major Joseph Woodruff, who in 1823 acquired the De Leon Springs property, when it was known as Spring Garden. These two springs contribute much to the freshwater marshes, streams, and lakes within the 21,574-acre refuge. Lake Woodruff and the surrounding wetlands became a refuge in 1964 to “preserve, improve, and create habitat for migratory birds and waterfowl, according to a 2002 U.S. Fish and Wildlife brochure.”

Entering the Refuge

The summer sky was an azure blue, sans clouds, when I drove down Mud Lake Road to the park. The road was straight and hard-packed, but because of large potholes, I drove in zigzags. The park road meandered through oak and pine habitat, past the Myakka and Live Oak trailheads and through a swampy area. I parked, I strapped my water bottle and binoculars to my belt, sprayed some bug repellent on my arms, legs and clothes, put on my large straw hat, grabbed my satchel and journal and walked through the opening to the marsh.

When I walked away from the tree line toward the first pool, I noticed how the cloudless sky surrounded the flat marshlands like a warm blanket. I walked a little closer to the water, which was bordered with tall sedges, rushes, and cattails.

The pools are connected by underground pipes with gates to manage water levels for the waterfowl. Park officials manipulate the water levels in the impoundments by flooding and draining “to discourage undesirable vegetation while encouraging desirable plant species.” These management techniques in the wetlands are said to benefit waterfowl, such as wading birds and ducks.

A swamp hibiscus has five pink petals, a maroon-colored central tube, and a long pistil reaching out past the petals, ending with a pink knob. The flowers open in the late afternoon and close by noon the following day. Photo "Hibiscus" by PMillera4 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Past the pond, a lawn-like grassy road led me along the east side of one pool. The water was low, revealing yellowish dried grass with some pockets of green vegetation. This was much different from my last visit in February, when the pools had more water. During that trip, I saw the blue-winged teal, a dabbler duck, sitting quietly on the cold water as red-wing blackbirds swooped overhead, disappearing into the cattails before making their common “congaree” calls. The sandhill cranes honked loudly as they flew in V-formations, and American coots gathered together by the hundreds. Along the pools’ edges, savannah sparrows darted in and around the swamp hibiscus.

Now, these birds were missing, and the embankments along the pool had overgrown grasses, fennels and sedges that ranged from three to six feet tall. Growing with the grasses were two different species of large pink hibiscus flowers. One species of hibiscus was called the swamp rose mallow, and the other was called the swamp hibiscus with smaller flowers. I could not help admiring the blossoms, which seemed to be blown up large as if they were under a microscope.

Trekking to the Tower

As I walked between Spring Garden Lake and a pool, a white peacock butterfly flew by me. The butterfly traveled fast, just a couple feet off the ground along the wild grasses. The bobbing and weaving of the butterfly on its impossible-looking course reminded me of my zigzag drive around the potholes earlier. Scientists say the erratic flight of the butterfly helps it elude birds and other predators. How differently the white peacock butterfly flew compared to the zebra longwings that floated through my backyard. The white peacock is a unique butterfly and thus not often confused with others; it is mostly white on the forewings and hindwings, with a few dark spots and dull orange scaling along the margins. I often see this butterfly by pond edges and marshes. Some of its affinity for wet areas no doubt comes from the adults looking for the frog fruit or water hyssop plants to lay their eggs on.

White peacock butterfly at Lake Woodruff pools. Photo by Andrea Westmoreland [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]

A black vulture perches on a frondless sabal palm at Lake Woodruff.

As I neared a tall wooden observation tower, I noticed a southern black vulture perched on a frondless sabal palm. Nearby were three more topless palms, each with a single black vulture perched on top. I wondered why the tops were gone from the palms. The apex, or heart of palm, is at the top of the tree where the fronds grow. It is sold in stores and restaurants, but once it is removed from the tree, the tree is doomed to die. It seemed unlikely that someone would take the edible tops from the trees in a wildlife refuge. Perhaps the palms had succumbed to old age, disease, insects or something else. These four scavenger birds were motionless and reminded me of those creepy stone gargoyles near the rooftops of old buildings. Even when I climbed the observation tower and had a panoramic view of the pools and lake, the vultures remained eerily still and silent.

I continued walking along the canal and stopped again to say hello to an older man taking pictures of a great blue heron fishing in the canal below. We both looked down at the wading bird craning his long neck over the water. The bird had a straight yellow bill and staring eyes; the neck was so long that if the bird had his head up, it would have been almost five feet tall. In fact, the neck vertebrae of this heron are of unequal length, forcing the bird to carry its neck kinked in an S-shape when flying and sometimes when at rest. I waited to see if the heron was going to spear a fish with its bill. Many times, I had seen the neck project the bill forward into the water with lightning speed and come up with a fish or frog attached to the open bill. The open bill gives the heron two points with which to hit its mark; in case it misses with one, the other may spear its prey.

A great blue heron at Lake Woodruff spears lunch. Photo by Andrea Westmoreland [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]

Wading through Flooded Flatwoods

I followed the trail west into a waterlogged piney flatwoods known as Jones Island. This was August, the middle of summer, and the rainy season for most of Florida. I left the open marsh to traverse trails that were as much as a foot deep in water. Young loblolly pines with an understory of the subtropical saw palmetto predominated on the island.

Walking along the grassy road, I saw an alligator in the distance. It moved across the surface of the canal waters and hid in some tall grasses. The sun was much higher in the sky now, and I had to stop a few times to wipe the sweat from my brow and to hydrate myself. Looking south was a postcard view of the marsh with many open miles of grass that ended in a horizon below the blue sky.

After walking about another quarter mile along this straightaway, I saw a red rat snake up ahead in the grass, sometimes called a corn snake. It is nonvenomous but known to bite. Its body was colorful, with gaudy deep-red and yellow-brown bands. I got out my binoculars to look closer at it. The snake remained very still; its head was lifted up a few inches off the ground and looking my way. I wondered what the snake would look like in motion, so I walked to the left toward the snake’s tail, and when I got directly behind it I gently grabbed the tail. The snake turned its head around. I jumped back a few feet and watched as it seemed to slither back and forth in one place, not going anywhere but producing a most unusual effect. Amazingly, the snake appeared to compress most of its body, making itself taller and flatter on the sides. When the snake slithered in the grass with its compressed body, it looked like a banner or ribbon turning and spinning as a kite tail would in the air. While I stopped in awe to watch its performance, it quickly slithered across the grass and disappeared. It seemed like the unusual movement of the snake was a ruse to startle me, so it had some time to escape.

Also known as the Eastern corn snake, this nonvenomous snake constricts its prey. Learn more. Photo by Moses Michelshon.

Red rat snakes are beautifully colored, so they have been very popular in the pet trade business. However, when this snake is encountered in the wild, it is often killed by humans who mistake it for the copperhead, which has similar markings. Its other common name, corn snake, was said to have come from its regular presence near grain stores, where it preys on mice and rats that harvest corn. This red rat snake would help control populations of wild rodents in the marsh.

When I drove out of the park and once again steered the black and white warbler in the zigzags around the potholes, I cheerfully recalled the erratic flight of a butterfly and the crooked backbone of a snake. I left the park feeling quite satisfied with the walk and lucky to have seen so much wildlife.

David Kyle Rakes has been a volunteer nature walk guide at Silver Springs State Park in Ocala, Florida, for the last five years. He is the author of Botanizing with Bears and Other Florida Essays, available to purchase at the Silver River Museum and Springside gift shop at Silver Springs State Park for $15. You may contact the author directly by emailing him at barakes123@gmail.com or writing to him at PO Box 2706 Belleview, FL 34421.

Jousting Tortoises: A Gopher Challenge!

To my surprise, the tortoises were face-to-face, ramming their shells into each other. The sky was turning a dark gray, and I heard thunder in the distance as these two tortoises battled it out…

Written by David Kyle Rakes

Adapted for Conservation Conversations by Marlowe Starling

They spend a considerable amount of their time underground in their sandy burrows, but during the warm days of summer, they become active. In my experience, if you walk through a sandy area of coastal or inland Florida any time between June and September, you can see these fossorial creatures lumbering about on land.

The gopher tortoise is an upland reptile species that lives in the scrub and sandhills of the southeast. Over the years of walking through Florida parks, I have seen many of them. I’ve seen some guarding their burrow entrance, walking down a trail, and even a few leisurely tortoises sitting and eating prickly pear cactus and grasses. Only once did I see them fighting amongst themselves; although I knew other animals compete for mates and territory, I was surprised to discover that gopher tortoises also exhibit this animal behavior. In males, tortoise fighting is known as jousting.

The eastern box turtle, which is commonly kept as a pet, is smaller than the gopher tortoise.

Credit: Eastern Box Turtle, Terrapene carolina carolina. (Jim Lynch, NPS; cc by-sa 2.0)

website for more info on box tortoises: https://www.welcomewildlife.com/all-about-box-turtles/#prettyPhoto

Before I tell you about the jousting tortoises, let me first tell you a little about this interesting animal. The tortoise is much bigger than a box turtle, which most people have seen. The top shell of the tortoise can be 14 inches long and is called the carapace; it is dome-shaped and brown or light tan. The bottom shell, called the plastron, is mostly flat and yellow-white. Both the carapace and the plastron are made up of square- to rectangular-shaped scutes, or hard plates. Up close, these scutes reveal their forming lines, rectangles within rectangles, which give the individual segments a decorative look. The tortoise has two large, round, stumpy hind legs and two flattened, shovel-like front legs that are used for digging their burrows. The head, when it is stretched out in front so the tortoise can eat, is snake-like, except for the beak-like mouth and eyes, which are large and proportional to the head.

Gopher tortoise burrows can provide habitat and shelter for more than 350 species. Photo by FWC.

The gopher tortoise is unique among other tortoises and their turtle cousins. The tortoise lives in multiple burrows within his area and doesn’t seem to mind sharing it with other animals. This is why the tortoises have been called “the landlord of the sandhills,” as they share their home with animals such as the indigo snake, pine snake, gopher frog, opossum, burrowing owl, Florida mouse, gopher cricket, and numerous scarab beetles. An interesting food chain has even evolved in the gopher tortoise’s home: The tortoise leaves dung there for dung beetles to eat, which in turn are eaten by the gopher frog. What an efficient way of taking care of waste, while also keeping a tidy burrow and providing food for other animals. It has also been reported that during the frequent sandhill fires, the burrows become temporary hideouts for birds and other creatures. There is plenty of room in the burrows since they are on average seven feet deep and fifteen feet long, with some as long as forty feet. The burrow is shaped like a cave from the tortoise’s body, so it is easy to determine the size of the tortoise in residence by the size of the burrow. The gopher tortoise’s scientific name, polyphemus, seems to reflect the cave-like burrow since there was a Cyclops named Polyphemus who lived in a cave in Homer’s epic poem, “The Iliad.” Perhaps the tortoise was named after Homer’s Polyphemus because both lived underground.

Because a gopher tortoise creates its borrow using its body, the size of a den can indicate the relative size of its inhabitant. Photo by FWC.

Tortoises emerging from their burrows are a barometer for a nice sunny day. Seeing the tortoise on a sunny day makes the day even brighter. The day I saw the fighting tortoises, however, it was overcast and rainy.

The two jousters were near the cabins at Silver Springs State Park. I was walking across the paved parking area and saw in the distance what looked like a tortoise in a grassy field. I walked over to see a tortoise resting by the tree line, but it saw me coming, and since it was close to its burrow, it raced off and slid down into its hole. I looked across the grassy area, and in the distance I saw two more tortoises. I had never seen so many tortoises this close at one time before, and these latter two seemed to be unusually close to one another. Tortoises live in groups, but they are mainly independent, so I tend to see them by themselves. I remember thinking that I might be about to see gopher tortoises coupling. I rushed over to a longleaf pine tree for cover, as I wished to observe them without revealing my presence. I was about sixty feet away, and in a good spot to watch them, so I took out my binoculars, leaned my back comfortably against a pine tree, and began observing the tortoises to see what they were up to.

The bony structure protruding from the front of a male gopher tortoise is called the lamina, used to joust other males for competition over territory and mates. Photo by FWC.

To my surprise, the tortoises were face-to-face, ramming their shells into each other. The tortoises were large adults over a foot in length, and I could hear the clamoring booms as their shells made contact. The sky was turning a dark gray, and I heard thunder in the distance as these two tortoises battled it out. The reverberations of the tortoise shells ramming into one another coincided with the thunder, making this fight seem like a great operatic performance. As I watched the tortoises it became clear that ramming was only one part of the battle. Both tortoises would begin the battle face-to-face; then, they would take turns lunging at each other, using their back legs to push off and their front legs to wrestle for position. After I watched them for a few minutes, it appeared that the tortoise that could lunge and get his lamina, or bony extension that protruded out from the plastron in front, underneath the other’s plastron or lamina was in the best position to roll the other on its back. Sometimes I would see both tortoises pushed up in front, their front legs up in the air, their shells poised together at the top at a forty-five degree angle, like two horseshoe leaners. Other times one tortoise had his lamina underneath the other’s in good position to flip, but the other tortoise’s front legs were on top of the potential victor’s legs, preventing the necessary lunge needed to finish the job. The tortoises’ lunging with the laminae has been described as jousting, the medieval competition between knights who wore suits of metal armor, carried a lance, and raced at each other on horseback. The objective was to knock the other off his horse with the lance as they rode past each other.

As it began to rain, the tireless tortoises continued to battle. Eventually, one tortoise succeeded in flipping the other on its back. The victorious one just stood and watched while the other lay helplessly upside down, thrashing its legs but going nowhere. I expected the victorious tortoise to walk away and leave the defeated tortoise upside down to die, but surprisingly, the victor began ramming the defeated one, and thus helped it to right itself again. The tortoises then went to battle some more and again the victorious one flipped his opponent upside down and, as before, rammed it and helped it right itself for the second time. This time the defeated tortoise, once he was on his feet, retreated and managed to get away. However, the battle was not over according to the champion, for it quickly crawled after the other, catching up to it and ramming it from behind. The defeated tortoise was forced once again to face off, and in less than one minute, and for an embarrassing third time, was put on his back. The winner as before helped the other back to his feet. The loser retreated again, but this time he was not pursued, so he made it back to his burrow along the tree line and disappeared underground. The champion tortoise also went back to his burrow, which was less than a hundred feet from the other’s. I always felt that the first tortoise I saw, the one that retreated right away, was a female, and the other two tortoises, who were of course males, were fighting for the right to mate with her. I’ll never know for sure since I didn’t get a good look at the first tortoise’s front plastron, which would have lacked a lamina if it were a female.

The rain stopped and the sun was coming out again when I left the tortoise battle grounds. Maybe someday a gopher tortoise will move into my yard and take up residence, like it has for one of my friends. I can only hope. I have the right kind of habitat: sandy soil, grass, and some pine trees, even a few prickly pear cacti in the backyard. It would probably also help if I could somehow convince my wife that we don’t need dogs, but she tells me that will never happen.

For more information about gopher tortoises, how you can help protect them, current research, news and more, visit https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/gopher-tortoise/.

David Kyle Rakes has been a volunteer nature walk guide at Silver Springs State Park in Ocala, Florida, for the last five years. He is the author of Botanizing with Bears and Other Florida Essays, available to purchase at the Silver River Museum and Springside gift shop at Silver Springs State Park for $15. You may contact the author directly by emailing him at barakes123@gmail.com or writing to him at PO Box 2706 Belleview, FL 34421.

Botanizing with Bears

About halfway up the hill, I stopped, because I saw something large and black on the trail. The animal had its head deep in the palmetto, and all I could see was a black shape…

Written by David Kyle Rakes

Adapted for Conservation Conversations by Marlowe Starling

One early morning in April, I went walking on the Florida Trail at Juniper Prairie Wilderness area in the Ocala National Forest. It was a day I planned to take my time walking so as to identify and study some of the plants and animals that were denizens of the scrub habitat. After paying to get in at the ranger station, I parked and walked about a hundred yards to where the Florida Trail crossed over the entrance road of the Juniper Springs Recreation Area. I walked off the road, turning right onto the Florida Trail heading west.

The sandy trail meandered back and forth as I walked through scrub oaks and Christmas-tree-like pines called sand pines. These trees were head-high level, or a few feet taller, and trimmed like a privacy hedge along the trail. It was like walking through a botanical garden labyrinth of trimmed hedges where one gets lost a few times before finding the way out.

The area is known as Big Scrub, a unique habitat in the Ocala National Forest known for the largest sand pine forest in the world. Trees and plants that grow here are smaller and have adapted to the poor sandy soil and oppressive heat.

As I continued walking the trail, it turned north with a long stretch of saw palmetto, rosemary and rusty lyonia. The saw palmetto was shorter than waist-high and most noticeable due to the pointed green to greenish-silver fronds that sometimes flicked back and forth as if trying to get my attention. The saw palmettos reminded me of the taller sabal palm, which is our state tree.

The rosemary shrub was here along the trail too, and it looked like an oversized tumbleweed, or something you would see in the American Southwest. The shrubs had small pine-like needles, and the numerous woody stems at the bottom grew out sideways. The plant has nothing to do with the herb rosemary that is used for cooking, though I suspect it was named after it because of the small needle-like leaves that look like the herb. A few years ago I found out there was a grasshopper, aptly named the rosemary grasshopper, which made its home only in Central Florida and restricted itself to living in the rosemary shrub. It has been most difficult to meet this grasshopper, which is only active at night and chooses to hide deep in the shrub during the day. Additionally, the grasshopper has brown and green body colors to camouflage itself, so it is even harder to find. This insect hides so well that it was not even discovered until 1928.

When I came out from the scrubby hedges, I found myself in a place with sandy soil and low-scattered vegetation beneath a wide-open sky. I continued walking north on the sandy trail, which took me near the top of a ridge for a panoramic view of low-growing myrtle oaks and saw palmetto. The scrubby vegetation on my left continued up the slope with tall, branchless dead trees or snags here and there. A nearby sign had a short paragraph about wilderness areas and told about a hurricane that recently came through and destroyed all the trees. The dead trees were standing as if in defiance of the hurricane.

“The trail beckoned...”

As I walked, a couple of red-bellied woodpeckers were flying and landing on the snags and making their familiar “chur-chur-chur” calls. Another woodpecker was nearby and at the top of a snag calling “qweeo-qweeo.” This was the not-so-common red-headed woodpecker, which to me seems more striking in comparison to the red-bellied woodpecker because its entire head and neck area is bright red, along with a white breast and black wings with white patches. Two blue and gray scrub jays took turns flying and landing on snags not too far from the trail, appearing to keep pace with me as I walked. Behind me, probably in the myrtle oak I had just passed, was the meowing sound of the catbird. These avian arias sweetened every step I made.

The trail beckoned, and I continued wading through a sea of saw palmetto. Here and there on the east side of the trail were some young evergreen pine trees, while on the west side the tall snags still prevailed. Surprisingly, I heard a summer tanager singing nearby, so I stopped to hear one of my favorite songs, “Break it up, tear it up, tear it.” The summer tanager is the only entirely red bird in North America. The birds are dimorphic; the male is red, and the female is a dusky yellow. These tropical birds are known for catching bees on the fly, and landing to remove the stinger before they eat the insect. They have made enemies of beekeepers in Central America. The birds not only forage heavily on the larvae and pupae of wasps that attach their paper nests to buildings, but they also seize domestic bees as they fly to and from their hives. Beekeepers fearing the loss of their hives have been known to shoot them. I began walking again and heard a similar summer tanager song, “Stay here, stay right here, hear me,” the sound getting fainter the further I went from it.

Wiregrass grew here, and in the wetter areas were the numerous carnivorous pink sundews and hatpins, or bog buttons. The pink sundews are a very different kind of plant in the genus Drosera. To think that we have plants that eat small animals is like having aliens come down from Mars to live here. There are not many plants that have evolved on Earth to work like an animal. There must have been hundreds of them living here in the wet, dark prairie soil. They had small, pink, five-petal flowers that grew from a smooth, short stem above their reddish basal leaves. These basal leaves looked dewy from the sticky secretions. The plant produces the secretions in order to trap insects, which they later digest.

Charles Darwin studied the sundews and made some unique discoveries. He was so fond of them he was known to have called one “my beloved Drosera.” Darwin found out that not only did the sundew feed like an animal, it also had muscles! When the sundew leaf was curling up to form a cup, the leaf was actually contracting its muscles, and to prove this he worked with botanist John Sanderson, who used a galvanometer to find that a definite electric current existed in the leaves of these carnivorous plants. Therefore, the sundew not only digested food like an animal but also moved like an animal!

After I had loitered around the wet depression, I turned around and walked back up the incline. It seemed amazing to me to see so much diversity. The prairie wetlands had much to see, and even on the slope that was hit by a hurricane, the birds and wildflowers seemed to be thriving. All of these plants and animals had unique adaptations for living here in the scrub and prairie, and it was a thrill to be able to see all this life around me.

About halfway up the hill, I stopped, because I saw something large and black on the trail. The animal had its head deep in the palmetto, and all I could see was a black shape. As I was trying to discern what it was, it backed up farther onto the trail and I could see it was a Florida black bear. The bear was about sixty feet away, its nose was moving in and out of the palmetto. It had thick black fur, a long snout and stood at two to three feet tall on all fours. This was the first time I had seen a bear this close in the wild, and though I was excited, I was also apprehensive.

I thought for a minute of what I should do, and since bears and most other wildlife are afraid of humans, I decided simply to let it know I was there. So I sniffed, loudly enough so the bear could hear me, and it worked, for the bear looked up at me. We both just stared at one another for a couple seconds; then, the bear turned around, made three low groaning sounds — “oool, oool, oool” — and dashed back into the palmetto on the other side. I could see the palmetto fronds moving back and forth as the bear retreated.

Not too far away, and separate from the other, more palmetto moved, indicating there was probably another bear with this one that I did not see. I looked around to see if I could see the bear, or bears, or any more movement in the palmetto. There was no movement at all, just all the palmetto growing under the big blue sky. When I was ready to turn around and walk away, a bear head popped up above the palmetto. The bear was standing up on its back legs, as if it were a circus bear performing for an audience. When it saw me, it dropped back down behind the palmetto and disappeared.

I left the bear and continued up the hill. I walked back to the trailhead thinking how fortunate I was to see the bear, and how much fun it was botanizing here. It occurred to me that bears and other animals are also botanizing when they search, taste and learn about what plants to eat. Even though bears are scientifically classified as carnivores, their diet is less than 10% meat. Most of a bear’s diet is comprised of nuts, berries and tender grasses and forbs. The bear I saw on the trail in the palmetto was probably looking for the berries of this plant. It was certainly a treat seeing a Florida black bear in the wild for the first time, and it could not have been more appropriate than in the wilderness of the Ocala National Forest.

David Kyle Rakes has been a volunteer nature walk guide at Silver Springs State Park in Ocala, Florida, for the last five years. He is the author of Botanizing with Bears and Other Florida Essays, available to purchase at the Silver River Museum and Springside gift shop at Silver Springs State Park for $15. You may contact the author directly by emailing him at barakes123@gmail.com or writing to him at PO Box 2706 Belleview, FL 34421.

Save the Salamanders, Save the Spring?

Salamanders & Wakulla Springs: frosted flatwoods salamanders have become a poster child for proper forestry management and a healthy longleaf ecosystem. Could they be the canary in the coal mine?

Save the Salamanders, save the Spring?

When we try to pick anything out by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe. - John Muir

By Derek Dunlop

Derek Dulop, a CFL intern, explores Florida’s underground caverns.

When I tell non-Floridians that I live in Florida, they immediately ask me how often I get to the beach or are jealous of how often I must visit the theme parks. Even living in Florida, I feel somewhat disconnected with how other Floridians must experience living in this state. As a wildlife biologist, I spend most of my workday outdoors, and when I’m not working, my free time usually involves exploring underwater caves. Compared with the homogenized developed parts of the state, I feel like many Floridians are missing out on the natural richness this state has to offer.

One of the factors that contributes to Florida’s natural diversity is its size. Living in Gainesville, I’m as close to the Appalachians as I am the Everglades in terms of driving time. While recently in Miami, I gave a rental car attendant my phone number. When he heard the 850 area code, he asked, “Where are you from?” “Tallahassee” I responded. He followed up with, “Is that in Florida?”

An 8-hour drive from Miami, just 45 minutes south of Tallahassee lies one of my favorite springs, Wakulla Springs.

Although seemingly similar to other springs on the surface, the scale of this particular spring is unique in the region. The most notable feature about Wakulla watershed is the vast network of underwater caves, one of the largest in the nation. If one were to unearth the limestone beneath the region, it would likely resemble a giant block of Swiss cheese.

A labyrinth of underground rivers and tributaries extending northward to Georgia makes up the Floridan Aquifer, of which Wakulla Springs is a part. Like veins transporting blood throughout the human body, these underwater passages transport water from around the region, with some passages being large enough to hold a jumbo jet. All of the water eventually emerges at Wakulla Springs State Park and flows roughly five miles into the Gulf of Mexico.

Locals frequently find relief in the spring’s waters during the hot summer months, but the constant 72-degree water also provides the most northerly shelter to overwintering manatees during the winter months. Manatees rely on the relatively warm spring water to survive when Gulf water temperatures become too cold. Despite somewhat low manatee numbers in comparison to Crystal River or Blue Springs, I enjoyed watching a mother and calf swimming in the basin from the park’s diving platform when I last visited in December.

View along the Wakulla River at sunset. Photo by Kari Nousiainen.

Later that day, during a boat tour offered by the park, I saw several more, among a few dozen alligators and an array of birds. Similar to boat tours at other springs, the park offers hour-long trips around the upper part of the river. I was lucky enough to experience the last tour of the day, and the setting sun provided great lighting for photographing wildlife. Not to mention, some very large cypress trees!

Although the Springhead of Wakulla has long been treasured as a recreational and natural marvel, the water has been under pressure recently due to fertilizer-laced runoff from the Munson Slough making its way into the system. This nutrient-rich water causes the spring to lose its aqua blue color, as it promotes algae growth.

Reduction in water clarity reduces the amount of light aquatic plants can receive, causing die offs. At one time, Wakulla Springs boasted the largest colony of Limpkins (a wetland bird that feeds primarily on apple snails) in the world. Now that the aquatic vegetation has disappeared, so too have the snails and, in turn, the Limpkins.

As the spring water flows south and mixes with the saltwater of the Gulf, it flows by St Marks National Wildlife Refuge. This diverse landscape houses an abundance of wildlife. However, this refuge is home to one species that is found nearly nowhere else.

The Frosted Flatwood salamander (Ambystoma cingulatum) is not the easiest species to come across. In fact, unless you are visiting during a cold rainy winter night you will likely never see one. Ambystomatid salamanders by nature love being underground, and this species, like others, only emerge during winter rains to migrate from the uplands to ephemeral ponds scattered among the longleaf.

The Frosted Flatwood salamander (Ambystoma cingulatum) is not the easiest species to come across. In fact, unless you are visiting during a cold rainy winter night you will likely never see one. Photo by Derek Dunlop.

Despite only surfacing during winter rains, Frosted Flatwoods Salamanders have become a poster child for proper forestry management and a healthy longleaf ecosystem. They act as an indicator for both properly managed upland and wetland habitat. For decades forest managers have focused their efforts on upland restoration, often needing to burn large amounts of acreage to get the best bang for the buck. Rules and regulations regarding burning have forced their hand to only burn during the wet winter conditions in order to prevent fires from becoming “wild”. Personnel and equipment too often become scarce during the summer months, since they often get sent out west to fight the ever more common wildfires there.

This collection of factors has meant that the ephemeral ponds these salamanders and countless other species rely on often never see the fire, which is needed to maintain them, since they are always full of water when the majority of burning takes place. Their relatively small acreage among the landscape, seemingly insignificant, has historically not warranted allocating supplemental resources to burn when dry. However, like a waterhole in the desert, these small habitat fragments have a profound impact relative to their size. Without fire, a diversity of trees including: sweet gum, oaks, and cypress never get knocked back. Eventually they become overly abundant, shading out the wetland and smothering the pond with leaf litter, which slowly breaks down into duff and later peat.

It’s this layer of peat that now is coming back to haunt forest managers. Peat fires, once started, can almost never be extinguished. They can smolder for months, billowing smoke into the sky and having the ability to spark new fires if left unchecked. This means that many ponds are now requiring intense and expensive physical restoration.

Researchers are working to collect, hatch, and head start salamander eggs in captivity. To date, over a thousand animals have been raised and released back into the wild. Photo by Derek Dunlop.

With their historical range once spanning the Southeast, Frosted Flatwood salamanders have been reduced to only a small handful of breeding sites, most located in the Florida panhandle. St Marks National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) boasts one of the best populations. However, the salamanders at St Marks NWR are still in a perilous state, especially after Hurricane Michael.

On October 10, 2018, Hurricane Michael made landfall as a Category 4 storm less than a hundred miles west of St Marks NWR. While the refuge was spared the brunt of the storm, storm surge caused numerous breeding ponds to become inundated with saltwater. How this will affect the salamanders is still unclear, but if the salamanders lay their eggs in salty water, they will likely not survive.

Now you maybe wondering, how is this salamander linked to a vast network of caves? Well one theory on why Wakulla Springs is turning brown points to the buildup of detritus in the ponds that filter into the Wakulla system. Remember the Swiss cheese I mentioned earlier? By not allowing fire to burn out the bottom of the ponds, the buildup of organic matter has slowed the rate at which the water is absorbed back into the aquifer. The peat is slowly leaching tannins into the water, turning the clear spring water brown. An effect so simple, it’s seen every time you make a cup of tea.

Save the Salamanders, save the Spring?

Photo of a Flatwood salamander egg by Derek Dunlop.

It’s worth a shot! My herpetology professor often exclaimed how amphibians made much better “canaries” than the actual bird in that ‘canary in the coal mine’ saying. Despite the gloomy outlook for the Frosted Flatwoods Salamander, restoration is underway. Researchers are working to collect, hatch, and head start salamander eggs in captivity. To date, over a thousand animals have been raised and released back into the wild. Land managers and governmental agencies are changing their ways and ponds are starting to see fire at the right time of year. Mechanical restoration is also underway and experimental ponds are being restored with the goal of providing additional habitat for head-started salamanders.

Back at Wakulla Springs, as my boat tour came to an end, I looked down into the abyss of the Wakulla headspring, having just enjoyed a magnificent tour of the river, I wished I could see the massive cave entrance that I knew was below my feet. It was tough to see past 30 feet on that day. I immediately thought about my time – on my hands and knees, digging through duff in nearby Apalachicola National Forest –trying to find a Tic Tac-sized, glue ball of Flatwood salamander eggs among the leaf litter. Could it all be linked? As the famous naturalist John Muir once said “When we try to pick anything out by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”

Saving Florida's Friendliest Native Bird Matters

Highly social yet quarrelsome, they’re like the stars of an avian soap opera. And they’re as brash and curious as precocious kids.

SCRUB JAY BLUES

Saving Florida’s Friendliest Native Bird Matters

At Oscar Scherer State Park, home to Sarasota County’s largest scrub jay population, the numbers have dropped from 160 birds to less than 20.

Republished with permission. Originally published in the January 2019 issue of Sarasota Magazine.

For the past 2 million years, Florida has been home to a superlative bird found nowhere else on earth. These birds are remarkably smart, with extraordinary memory and perhaps even the ability to plan ahead. Highly social yet quarrelsome, they’re like the stars of an avian soap opera. And they’re as brash and curious as precocious kids. Many a jubilant birdwatcher has turned to find one mischievously perched upon their shoulder.

Despite decades of conservation efforts, the Florida scrub jay remains an animal at risk. In the two decades after the species was classified as threatened in 1975, the population dwindled by 90 percent. Since 1993, it has dropped another 25 percent. Now just about 8,000 Florida scrub jays remain in the state. At Oscar Scherer State Park, home to Sarasota County’s largest population, the numbers have dropped from 160 birds to less than 20.

Part of the problem is that scrub jays, like many Floridians, are picky about where they live, preferring undeveloped scrubby flatwoods, where small scraggly oaks and saw palmettos take root in fine white sand dunes. “Scrub jays like scrub,” says Tony Clemens, park manager at Oscar Scherer. “And they like it just right. I call it the ‘Goldilocks zone.’ Not too short, not too tall, not a lot of pines. They’re very particular. They won’t live in any other type of habitat.”

But scrub habitat is high and dry, making it desirable for developers and long pitting the state’s ancient avian natives against more recent, sun-seeking arrivals.

Still, across the state, land acquisition, restoration and management programs have sought to protect the species and its habitat. Controlled burns, which use fire to naturally revitalize scrubby flatwoods, have become an essential part of the conservationist’s toolkit. Meanwhile, programs that ship the birds to new locations across the state have helped diversify the gene pool of distant populations.

There have been some successes. At Duette Preserve in Parrish, thousands of acres of scrub habitat have been acquired and improved. And at Archbold Biological Station near Lake Placid—where scrub jays are the subjects of one of the longest continuous studies of a bird population—the scrub jay’s future looks hopeful. A handful of these strongholds scattered across the state may be the species’ last hope for survival.

The species is especially threatened in isolated locales like Oscar Scherer that inhibit genetic diversity. “I’m a very optimistic person, but I don’t ignore the data,” Clemens says. “It’s important for people to realize the dire needs that we have for the Florida scrub jay. I consider it the canary in the coal mine.”

Scrub jays are part of a vanishing ecosystem that also includes threatened wildlife like the gopher tortoise, Florida mouse, scrub lizard and sand skink, so conservation efforts that protect scrub jays protect these animals as well.

“If you’re doing management that benefits scrub jays, you’re also managing a whole bunch of other interesting and unique species in Florida,” says Craig Faulhaber, the Avian Conservation Coordinator for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Oscar Scherer pushes for education and outreach programs to bring attention to the species. Though the park’s urban location makes it tricky for scrub jays to thrive, it gives locals a place to come into contact with these birds. Every Sunday morning Clemens hosts a guided scrub jay walk and once a month welcomes volunteers to help take a census of the park’s population.

Since 2000, the park has also hosted the Scrub-Jay 5/10K Race to raise money and awareness for the bird. The race kicks off this year on Jan. 12.

Sending the Blues Away

For nearly a decade, no one could find a Miami blue and it was eventually feared extinct. Then, an observant butterfly aficionado at Bahia Honda State Park noticed a butterfly that looked different than any they had seen there before. It was a Miami blue!

by Peter Kleinhenz

“Doomed to extinction,” “irreversible decline,” “extinction is forever.” Those words are like lightning bolts that strike down periodically from the clouds of depression that follow me in the wake of animal extinctions. Species that have taken millions of years to evolve to their current state disappear, in some cases, in just a few generations due to habitat loss, invasive species or poaching. Nothing makes me sadder or more pessimistic.

Few intact coastal habitats remain in the Florida Keys. Photo by Geena Hill.

A pair of Miami blue butterflies mating. Photo by Florida Museum of Natural History.

Miami blue butterflies in captivity start their lives as tiny caterpillars in little plastic cups. Photo by Florida Museum of Natural History.

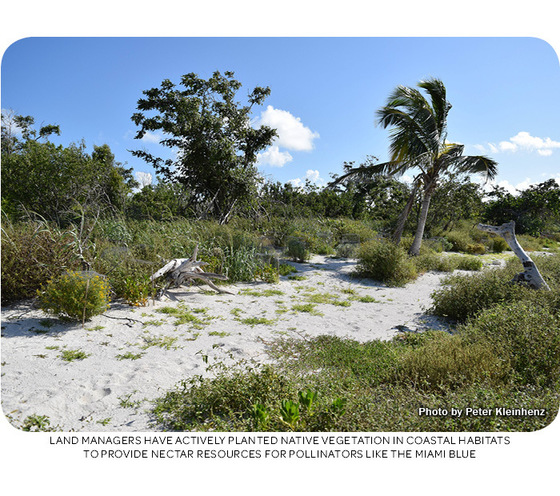

Land managers have actively planted native vegetation in coastal habitats to provide nectar resources for pollinators like the Miami blue. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

Miami blue caterpillars are tiny and delicate, and extreme care must be taken during their reintroduction. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

A Miami blue caterpillar explores its first wild leaves after its reintroduction. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

Wild cage protects planted dune vegetation. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

Sarah Steele Cabrera shows a young Miami blue to a nearby landowner. Photo by Peter Kleinhenz.

Researchers at the University of Florida prepare tiny habitats for young Miami blue butterflies. Photo by Tedd Greenwald.

Ants help protect the Miami blue from predation, while “farming” the caterpillars for their sweet secretions. Photo by Genna Hill.

The good news is that the electrified words mentioned above are not always true. Take the Miami blue butterfly. This diminutive insect once ranged from Tampa Bay south to Key West, fluttering from flower to flower in dry, coastal habitats. Miami blue females lay up to 300 eggs and, historically, they were limited only by the availability of their host plants and predation. Then humans came along.

Dry, coastal habitat equated to prime real estate for many, and it didn’t take long for Miami blues to disappear from virtually all of their historic range. The reason for this decline stems from an unfortunate aspect of Miami blue mobility. The butterflies rarely range away from the beach vegetation where they first emerged out of eggs. Once habitats became fragmented from one another, the chances of a Miami blue finding a non-sibling mate were almost impossible. By the time I was born in 1990, this butterfly could only be found among the vegetation along a few undeveloped beaches in the Florida Keys.

Then Hurricane Andrew hit. The Category 5 hurricane slammed into South Florida in 1992, obliterating much of the remaining habitat of this tiny insect. Under natural circumstances, populations in destroyed areas would be replenished by other populations nearby. This was no longer possible and, so, with the hurricane went the Miami blue.

For nearly a decade, no one could find a Miami blue and it was eventually feared extinct. Then, an observant butterfly aficionado at Bahia Honda State Park noticed a butterfly that looked different than any they had seen there before. It was a Miami blue! Subsequent surveys showed that approximately 50 Miami blues survived in less than 1 square mile of habitat.

Conservationists immediately rushed into action.

Wild specimens were collected and lepidopterists who study butterflies at the University of Florida created a captive breeding colony. The plan from the beginning was that offspring from this group would be used to create new populations in suitable habitat. But, first, you need suitable habitat.

Miami blues, like all butterfly species, rely upon certain plant species that serve as “hosts” for their caterpillars. These little munching machines have a voracious appetite for gray nickerbean, blackbead and balloonvine. The adults are more liberal in their food choices, sipping nectar from many types of flowering plants. As such, there is a direct link between healthy wildflower populations and healthy pollinator populations. This fact has informed the management of an area that will likely become crucial to the Miami blue butterfly’s survival.

Florida Keys Wildlife and Environmental Area (WEA) consists of 4,250 acres, scattered from Key Largo to the Lower Keys. Some of these acres represent pristine examples of imperiled natural communities. Others have a long way to go. One such site, a degraded beach on Sugarloaf Key, was covered in an exotic plant known as scaevola. But area biologists Jeanette Parker and Susie Nuttall saw potential and got to work.

“Whenever we plan a planting project, the first thing we do is identify the habitat type such as hardwood hammock, coastal berm, mangroves, etc.,” Susie explained. “I take inventory of what native vegetation is already growing there, how well it is doing and what its sun, soil and water requirements are. This allows me to create a list of species that should be growing on the site. From this list, I then narrow it down by what plant species are threatened or endangered, which plant species will benefit wildlife species that are threatened or endangered and, in the case of this beach site, I look at what species will provide increased beach stabilization.”

Planting a variety of plant species helps the many wildlife species that depend upon these plants. One species that Florida Keys WEA biologists had their sights set on from the beginning was the Miami blue.

“Every organism that is associated with an ecosystem plays a vital role to the health and stability of that ecosystem,” Susie elaborated. “When one piece of the ecosystem is missing, often unintended or unknown negative impacts occur and sometimes we don’t realize it until it’s too late. Butterfly species, such as the Miami blue, are believed to be better pollinators than bees. Recent studies show that we are seeing large declines in insect populations, so we hope that by creating the conditions to restore one species, we can benefit other species as well.”

Susie and Jeanette planted a suite of species onsite to do just that. They surrounded the plants with wire cages to protect them from hungry (and nonnative) green iguanas. And then the wait for the missing pollinators began. It lasted until a fortunate set of circumstances unfolded, right when I happened to be in the area.

A few weeks ago, I was down in the Keys with my coworkers to conduct site visits for new visitor projects in the area. The three of us were working on things that weren’t article-worthy when Jeanette, the lead area biologist, received an exciting phone call. It turned out that the woman on the other end of the line, Sarah Steele Cabrera, is a lepidopterist at the University of Florida and she had some leftover Miami blue caterpillars from another project. Did Jeanette want some?

Of course she did, and she kindly invited Catalina, Melissa and me to take part. Just a couple days later, we met Jeanette and Susie early in the morning for a small-scale, but significant, act of conservation.

We reached the end of a road in a neighborhood right by the coast. Sarah met us there, along with a landowner whose property bordered the patch of coastal habitat we would be visiting. I watched as Sarah, Susie and Jeanette talked with the landowner about the value of conserving Miami blues and restoring habitat. The evidence that conversations like this matter surrounded us. Native pollinator plants, water features and bird feeders indicated that this landowner wanted his home to be an extension of the natural ecosystem that surrounded him.

Sarah went to her car, grabbed some foam cups and held them out for us to see. She peeled back some netting to reveal a cluster of small leaves and even smaller caterpillars. They were Miami blues and were at the end of a lengthy journey.

Students in the University of Florida lab of Dr. Jaret Daniels have been raising Miami blue butterflies in captivity to provide stock for future releases. A couple of weeks before our visit, such a release occurred at Long Key State Park. The cup Sarah held in her hand housed “leftovers.” The little green and brown specks didn’t look like much but, after Sarah gave us more details how these caterpillars got here, we didn’t doubt their value.

Susie added, “When we read articles about [Miami blue] reintroductions, like the recent one at Long Key State Park, we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg. The process is a long road and includes an immense amount of work from dedicated people to get funding, raise thousands of larvae in a lab, monitor wild populations and coordinate between various institutions and agencies, permit applications, etc.”

The six of us trudged through vegetation that ultimately opened up onto a beach, facing the deep blue water that separated us from Cuba by only 100 miles. The beach was punctuated by metal cages that surrounded unusual plants including sea lavender, Joewood and inkberry. These, Susie noted, were planted just a few months ago. All were spreading beyond their cages, establishing themselves on one of the few truly natural beaches in the area. The stage was set. The only thing missing were the actors.

Sarah walked Susie and me up to some gray nickerbean. She opened the cup, took out a small paintbrush and allowed a caterpillar to crawl onto the bristles. Sarah then placed the brush next to some leaves and prodded the caterpillar to crawl onto the first wild vegetation it had ever felt.

We collectively scattered caterpillars on any gray nickerbean or Florida Keys blackbead we found until Sarah’s little cup was empty. Now, the caterpillars were on their own. Well, sort of.

Miami blues have a symbiotic relationship with certain ants that keep them safe from marauding parasitic wasps. In return, the ants “milk” the caterpillars for sweet secretions. The team hopes that ants will find these reintroduced caterpillars and keep them safe for the month or so that it takes for them to transform into butterflies. While not necessarily essential to Miami blue survival, this relationship illustrates the fact that reintroductions consist of more than simply releasing a bunch of animals back into the wild. Any animal's strand in the web of their ecosystem must be fully considered for a reintroduction to truly succeed.

I’ve thought a lot about that morning since it happened. I, and many others who work for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), consider conserving wildlife to be the prime motivator for why we are in this field. To take part in it so directly was immensely rewarding and restores my faith that maybe we can turn around the current trend of species extinctions.

I asked Susie several days after the reintroduction what she thought about it. She told me simply, “Being part of a reintroduction of a species that was once thought to be extinct is and will be one of the highlights of my career.”

I’d have to agree. For it seems, with creativity and dedication, extinction can sometimes be just temporary.

Discover more details about the

University of Florida’s work to conserve butterflies:

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/miami-blue/

FWC has numerous resources to learn more about butterflies and ways to help their populations. Visit the Great Florida Birding and Wildlife Trail website to find places to observe butterflies and get rewarded for finding new species. For tips on observing butterflies in one of the best places in the state to see them, visit the Big Bend WMA Butterfly Guide page.

Be sure to join our Pollinators of Florida project on Florida Nature Trackers to add your observations to our statewide database. Finally, you can help butterfly populations by planting a refuge for wildlife or joining us in our Backyards and Beyond campaign.

Learn more about Backyards and Beyond

and the City Nature Challenge.

Nayfield Acres: A Conservation Story

It was truly a pleasure to have worked with Conservation Florida.” We worked with Kc Nayfield and his wife Marybeth to protect 136 acres of land adjacent to the Big Shoals Conservation Area that contains a seepage spring and creek system that drains into the Suwannee River.

A Conservation Story

White Springs, Hamilton County, FL

K.C. Nayfield, DVM, is a well know Crystal River veterinarian, musician and outdoorsman. He serves on Conservation Florida’s Board of Directors.

Since I am a native Floridian I have witnessed a lot of changes in my state over the last 66 years having seen the population swell from just 3 million residents to over 20 million. As a part time wildlife veterinarian and founder and former director of a wildlife rescue group I developed a great appreciation for our magnificent and wonderful native species. As an outdoorsman and fisherman I have come to appreciate how delicate Florida’s environment, natural beauty and natural resources are and the need to conserve and protect them.

So it is really little wonder that when I found myself with some disposable income I wanted to put it into land conservation. Marybeth agreed and we began the hunt for environmentally sensitive property to purchase.

We started looking around the upper Suwannee River and Santa Fe River areas in North Florida. When we camped at Stephen Foster State Park, the Folk Culture State Park, we fell in love with the old town of White Springs and the upper Suwannee. We decided with limited funding our best impact would be to purchase property adjacent to Suwannee River Water Management lands. We were lucky to find a 136 acre tract just north of town that the owner was anxious to sell. We closed on the property in October of 2009. It had been planned to be a mini-farm development.

The land was at one time a working farm and had been for almost 100 years. They grew crops, ran cattle and had tracts of planted pine. There are even remnants of an old farm house from the 1930’s.

We had attended a meeting sponsored by Conservation Florida (formerly Conservation Trust for Florida) where the members explained the process of protecting property through the use of a conservation easement (CE). We contacted them and began the process.

We also had an officer from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) come out and inspect the property. Her name was Kris and she was extremely informative and would put together the property management plan required to get the CE.

There are good tax incentives for putting property into a CE and they depend on how much one limits the development. We expressed our desires to Conservation Florida and they included no houses, no mining, some agriculture, a small pole barn, a bridge and possible boardwalks, planted long leaf pines, hunting and other recreational activities. We worked through the documents and did have to pay a bit to get the CE. This money would cover the future yearly inspections required to steward the land. My accountant crunched the appraisal values for the tax relief and thus Nayfield Acres was founded.

There were several projects that needed to get started immediately. The first was to get the long leaf pines in the ground during the following winter when the trees are dormant. We opted to plant 5 areas for a total of about 25 acres and close to 23 thousand trees. We had the pastures furrowed and planted containerized tublings instead of bare root seedlings to get higher survivability. We even received a small incentive from the State for our efforts.

One of the next issues was to remove old barbed wire fencing. We learned at closing from our lawyer that old fences can overrule survey results in a property boundary dispute. Also I had seen firsthand the effects of fences on wildlife and wanted as much as possible off the property. Our first experience involved tying the wires to the hitch on the back of the truck and gunning the engine. To my amazement the posts and wires came popping off and out of the ground. Pulling the wire off the posts was another issue and wrapping this nasty stuff into balls and coils was difficult to say the least. To this date we have removed over 1600 pounds of barbed wire and recycled it in Lake City for a penny a pound. There is much more to be removed since every time the old fences failed the farmers did not remove and replace but simply added another row of fence.

The northern part of the property is about 30 acres of cypress swamp. In the early 2000’s the owner logged the trees out of this area. To do so required bringing in the massive skidders to haul the trees out. These machines left huge gouges in the swamp as seen from the aerial views. We enquired about having this area restored but the permitting process and expenses were exorbitant. Also after 18 years the native cypress trees are just starting to rebound now. It is Ironic that to log the swamp and destroy and ecosystem needed no permitting or payments.

The swamp was also used to refill the cow pond on the southern end of the land. A ditch was cut to channel the water to the artificial pond. We filled in the ditch to maintain water in the swamp as nature intended it to be.

After a year or two it became apparent that we would need a tractor to maintain the land so we built a small pole barn using recycled posts and rafters from our old boat house at the mouth of the River. We had a well drilled and ran the pump from solar panels storing water in an elevated tank. Since that construction we enclosed a bathroom and shower area. The toilet is a composting toilet which requires no water or drain field. You simply do your business and add a half a cup of a saw dust material and spin the drum. A solar powered fan helps in the composting process and there are no odors. We opted for an in line propane heater for the shower but are still having some issues with getting proper water flows and heat.

A couple years ago we installed 8 solar panels, 4 large batteries and an inverter system to generate AC electricity. It has allowed us to run small appliances and tools as well as recharge the electric ATV that we use to work and drive around the property. It would have cost a lot of money to run power lines out to the barn and above all we just didn’t want to see them on the property. Having a limited energy supply has made us very conscious of energy usage and conservation. When we bring the truck camper up we still need to use some propane but the solar power has decreased the usage of fossil fuels dramatically.

Another huge issue we faced early on was the invasion of the Chinaberry Trees. These are non-native, grow extremely rapidly, produce poison berries, choke out other native species of trees and harm wildlife. One area of the property had so many that we called it “Chinaberry Town.” Over a couple weekends in a September 8 years ago we came in with chain saws and herbicides. Basically we would cut down the trees and poison the stumps. We probably killed over 75 trees and some were a foot to a foot and a half in diameter. We learned the next year that this would not be the end of it. The berries can stay dormant for apparently a couple years and some of the trees grow off of “runners” which make them difficult to kill. So every September or October we still are killing Chinaberry trees although they are now usually less than 8 feet high or are saplings. Yes, they can grow to a height of 8 feet in a year! We are now killing them before they are able to mature and produce more seeds.

We have really managed to enjoy the property. Many times we have friends join us for a weekend of camping, work, canoeing, and sometimes hunting. We do allow the harvesting of a few deer and wild turkeys each year. We love our daytime visitors in that we can give tours in the ATV and explain about conservation and wildlife protections. If we are lucky we can see deer, turkeys, hawks, gopher tortoises, armadillos, quail, butterflies and many different birds. Our CE inspector identified an uncommon snake called a Florida Red Belly a couple weeks ago. At night we are serenaded by the tree frogs from the swamp, owls hoot and coyotes occasionally call.

“It was truly a pleasure to have worked with Conservation Florida. ”

It was truly a pleasure to have worked with Conservation Florida. Marybeth and I met their president and executive director for dinner a couple years ago and to my surprise I was asked to serve on the Board of Directors. I have since assumed the job of secretary for the organization. In the last couple years I have had the pleasure to give Power Point presentations on Conservation Florida to several civic groups in Citrus County.

In giving these talks I try to express the need for much more conservation of environmentally sensitive lands. We are at a crossroad in Florida and need to act now. The real need is to connect wildlife refuges, parks and conservation areas together with wildlife corridors as documented in the films produced by the Florida Wildlife Corridor project. You can visit them on the internet. Here at home we need to connect the Withlacoochee State Forest with the Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge.

Funding for land purchases in the State through the Florida Forever program has been slashed drastically over the past 8 years and there is no relief in sight. This is in spite of the passage of the Florida Water and Land Conservation Amendment in 2014.

This has put the pressure on private land saving groups like Conservation Florida. I now know firsthand how much work, time, money and efforts go into getting this done. Conservation Florida has managed to protect over 25,000 acres of land since 1999. We are always in need of contributions to continue our work. Currently we have an executive director, an assistant director, a director of conservation, two consultants and four interns on staff. We have an operating budget near half a million dollars and we are the only regional land trust in the State accredited by the Land Trust Alliance chartered to work state wide.

I am asking that this coming Giving Tuesday that you consider helping us by making a small gift. You can do so on social media or by visiting our website at conserveflorida.org. Let us keep Saving Florida. For Nature. For People. Forever.

Butterflies to Black Bears: a Bioblitz in the Florida Wildlife Corridor

your questions, answered! 🐝

On October 20th, we’re hosting our statewide bioblitz: Counting on the Corridor! We’re connecting Floridians with the beauty and biodiversity of three conserved locations within the Florida Wildlife Corridor to highlight its incredible biodiversity, and ultimately the need for further protection. While we explore, we’ll be collecting useful data at three diverse habitats that are all critically necessary to our State.

At our upcoming bioblitz event, you can learn more about how Conservation Florida is saving land within the Florida Wildlife Corridor. You'll also have the chance to interact with Florida’s native species while learning from expert naturalists, and the data you collect could be useful in protecting the plants and animals that make up our unique ecosystems.

We thought you might have some questions, like:

What in the world is a bioblitz?

Our bioblitz welcomes people from all backgrounds to explore the land, engage in science, and connect with some of Florida’s most special places. It’s an opportunity for citizen scientists and experts alike to explore nature to find, count, and identify the biodiversity in an area. Participants come together to find, COUNT, and identify as many species of plants, animals, microbes, fungi, and other organisms as they can spot! You can learn more by watching this short video.

Florida is home to many unique species and diverse habitats. Counting on the Corridor allows citizen scientists of all skill levels and ages to explore pristine coastlines, crystal-clear springs, and open prairies. During our statewide bioblitz, the community of citizen-scientists will work with subject matter experts to count wildlife in three very different habitats.

We will have activities throughout the day that are designed to be fun and informative for families, community groups, and people of all ages and abilities.

OK, now what’s a wildlife corridor?

While the term “corridor” isn’t quite a buzzword, it may be one of the most important topics we can bring to the table in the conversation about conservation. Sometimes called a conservation corridor or greenway, a wildlife corridor is a piece of land or a habitat that links together two larger wildlife habitats. These connectors, if you will, allow wildlife to migrate and disperse on a large-scale. Corridors are crucial in Florida because they make sure local animals, like the Florida panther and the black bear, can move about freely. These pieces of land that serve as bridges between large, protected lands keep our biodiversity strong.

Now the question is, why do they matter?